If you have ever checked the “Behavior” section on VirusTotal’s review of a sample, you have seen how it may flag suspicious activities performed by the executable you are analyzing. Irrespective of the number of detections that your sample gets (even if it gets no detection at all), this VirusTotal report may still indicate that it somehow recognizes it is doing weird stuff that you would ideally like to keep concealed…

For this article, I have created a very simple PoC which simply calls VirtualAlloc() and VirtualProtect() to stage a memory space. It is doing so using very common code snippets to get the API address dynamically by walking the PEB. This technique is used extensively in many frameworks and tools, SysWhispers or available Cobalt Strike UDRLs to name two common ones.

Note: the purpose here is not to discuss the specific technique of walking the PEB, which has been extensively covered in many places, but to review how these code patterns are flagged by security solutions, and how to deal with this as a red teamer.

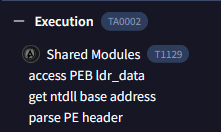

As seen below, heuristic analysis is able to determine that this sample is parsing PE headers:

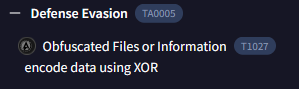

Another IOC that pops up, but which I won’t address below, is that it detected the use of xor:

All of these indicators will no doubt contribute to tilt the balance towards “suspicious” when an EDR reviews what your code is doing. And needless to say that if suspicious behaviors like those can be identified in the building blocks of your loaders, implants, etc…, then the chances of detections during an engagement in a monitored environment will be high. What checks are performed exactly and what can we do to avoid them ? This is were CAPA, from Mandiant, comes into play.

Meet CAPA

CAPA is a Mandiant tool primarily designed for malware analysts and which looks for suspicious code patterns in order to help get a quick intuition as to what an executable might be doing. It is based on rules (that you can contribute to, should you wish to), similar to YARA rules but for assembly bits and bobs rather than raw bytes. In our case we can leverage them to understand better how our code gets flagged.

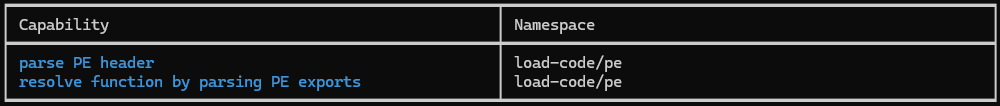

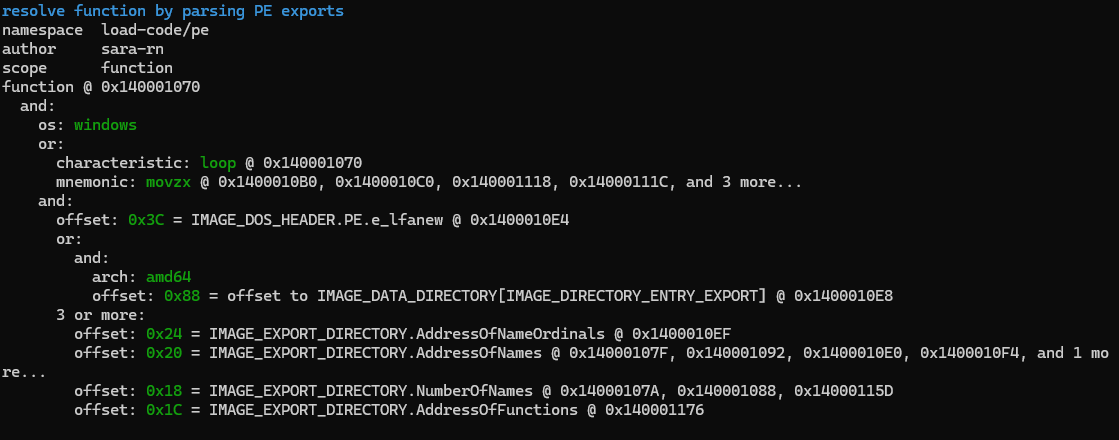

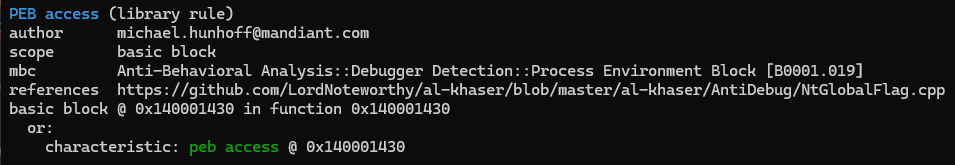

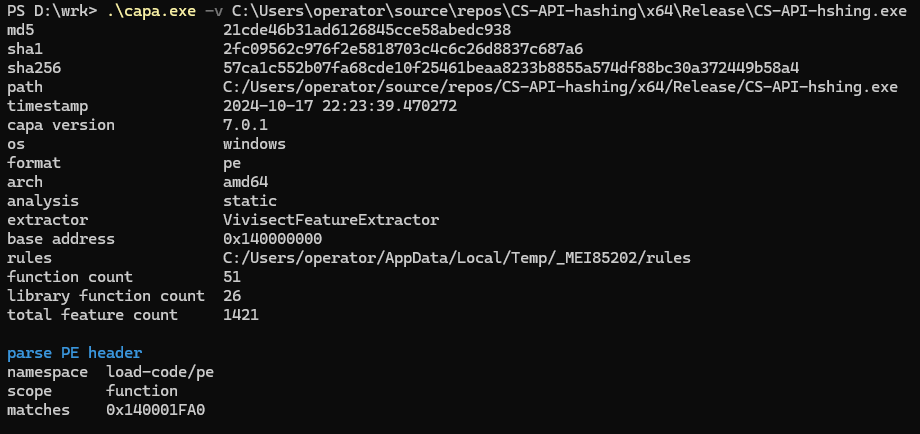

Running the tool directly against the executable will confirm what we saw in VirusTotal but more importantly the -vv option will display details about the rule and the offending code snippets.

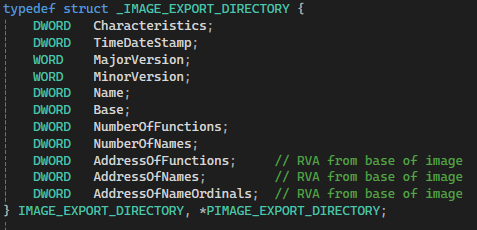

This particular rule tries to recognize that something is walking the PEB, by identifying well-known offset values that are omnipresent in any implementation of those techniques: e_lfanew, IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT, etc… For instance, the suspicious 0x20 and 0x24 offsets are for AddressOfNames and AddressOfNamesOrdinals in the _IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY structure visible below.

Accessing those fields means those offsets are present in the assembly instructions as it adds them to registers, and these types of code snippets are very frequently used in the malware development space.

Locating the problematic code

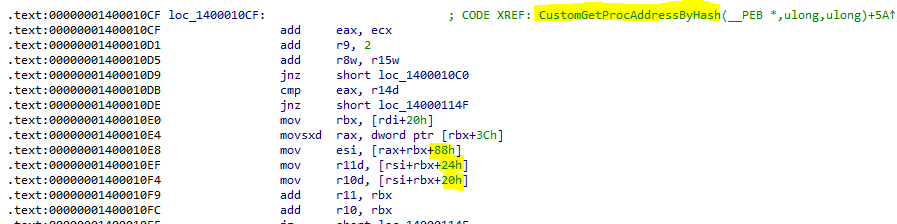

Let’s fire up IDA and check what’s going on at with this 0x140001070 function that CAPA flags. I’ve compiled with debugging info present to make it more obvious and we can see immediately that the rules fires on snippets present in CustomGetProcAddrByHash(), which is full of those suspicious 0x3c, 0x88, 0x24 offsets as the function parses the Export Directory:

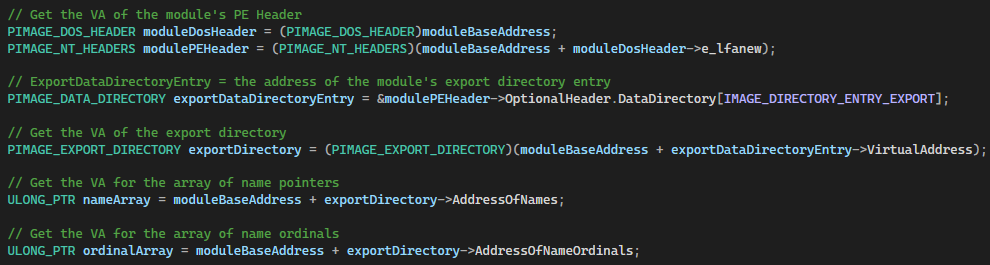

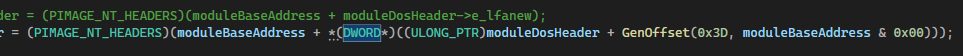

These few lines match the following bits walking the PE structures all the way to the Export Directory and the Addresses of Names or Ordinals:

At that point, it becomes obvious which steps should be taken to slightly confuse the type of analysis: we need to avoid hard-coded offsets and have something more dynamic. There are many options but the one I will use here is a simple call to function such as GetNameOfOrdinalsOffset() which will pretty much do anything possible as long as it returns 0x24. Don’t make it too simple though otherwise the compiler will optimize that code in such a way that you’ll be back to simply adding 0x24 straight-away. Be creative. Make it conditional on the environment, etc…

Additionally, CAPA also has a rule to detect the assembly code which locates the PEB in a process: __readgsqword(0x60). This makes sense, since this instruction is indeed the starting point for most of the code snippets out there for malware development in Windows…

Implementing a bypass

Here, I have created a separate GenOffset() function to return the offset values dynamically at run time in order to have static hard-coded values as seen above. The original implementation is commented out, the new one using that function is visible just below. Instead of directly adding the e_lfanew offset, we have that offset produced at runtime by our new function:

Do note, though, that the optimizer might still be able to see through this and optimize your code in such a way that it ultimately replaces the function call with the raw offset. You will need to either disable optimization or make your extra-function dynamic enough that it cannot be replaced by a hard-coded value (the preferred option of course…).

What it does is not important and you would have to implement it yourself as copying it from somewhere else would defeat the whole purpose that we are discussing here.

Removing the .pdb file generation and rechecking with CAPA, we now find that our red flags are gone !

The parse PE header indicator seems to be a false-positive which applies to pretty much any executable and can be ignored.

I also mentionned at the beginning, that the use of xor operation has been detected… you know what to do !

Summary

We have seen how Blue Team tools can be leveraged and perform simple checks on offensive tools. WinDefender and YARA rules are usually taken as references for these types of checks, but CAPA gives an alternative view on your executables. This can help avoid silly detections early on during an engagement and should be added to the list of OPSEC checks your implement on your toolset.