Cobalt Strike keeps on evolving and this has serious implications on what happens behind the scenes when your payload runs, and what the resulting IOCs will be. With the growing complexity of the product there has also been a lot of confusion around which part of Cobalt Strike does what. The answers are generally in the documentation or in the (excellent) blog posts in three parts, but not immediately available and it takes some time and effort going through them before you gradually put the pieces of the puzzle together.

With the latest 4.10 release and the introduction of BeaconGate, I will go through the process of customizing the implant using those features, and highlight the associated IOCs.

As a bonus, this will also demonstrate the use of a little-known Windows API to implement sleep without using Sleep() or WaitForSingleObject().

A bit of history

The amount of features, functionalities, with all of their subtleties, can be daunting for anyone looking at Cobalt Strike as of 2024. This is best understood if you look at this as being the result of years of releases and additions. A key thing to understand is that Cobalt Strike rarely retires things, even once they have clearly become bad opsec. An example is the “fork & run” feature, which was a great innovation for a time, but that era is now over. You can still use it though. So let’s quickly retrace what happened, at a very high-level.

It all started with the ability to replace some strings via the Malleable profile but these days are long gone now if you are trying to evade modern security solutions.

At some point, the Artifact Kit also enabled you to customize some of the code used by Cobalt Strike but eventually, many signatures were released which target bits of codes that cannot be changed that way, such as the Reflective Loader or the Sleepmask.

The ability to customize Cobalt Strike then focused on those two components, by letting users write their own Reflective Loader (UDRL) and Sleepmasks.

Generally speaking, your starting point should be to use a UDRL and a custom Sleepmask. You would then rely as much as possible on BOFs when actively interacting with your beacon. To know what runs as BOF, or as API, or via other ways, keep an eye on this documentation.

The latest releases this year have changed how the Sleepmask is implemented, and have also introduced “BeaconGate”… which offers nice capabilities but can also provide a very easy way to get caught if you are not fully aware of where that runs and how, as we will see in examples below

Sleepmask and BeaconGate

Accompanying the 4.10 release, Sleepmask-VS was released, containing a generic code template for developping BOFs in general, with a strong focus on demonstrating of Sleepmask and Beacongate are implemented. To summarize, Sleepmask contains the code responsible for obfuscating Beacon (and its Heap records), sleeping, then de-obfuscating. BeaconGate is a new mechanism used to “proxy” certain API calls so that instead of being run from your Beacon, they are run from this BOF which is setup differently, and more importantly, in a different memory location. Note that the two run within the same piece of code, which supports both functionalities.

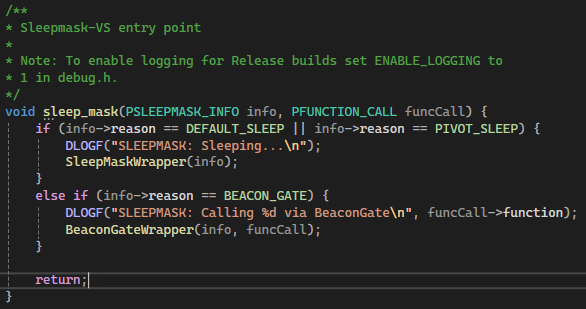

You can in fact visualize this in the sleep_mask() function whichs checks whether it has been called to Sleep, or to run BeaconGate:

This has been nicely arranged in Visual Studio so that you can compile your BOF in Debug mode, which will run it as an executable mimicking the BOF being run by a beacon.

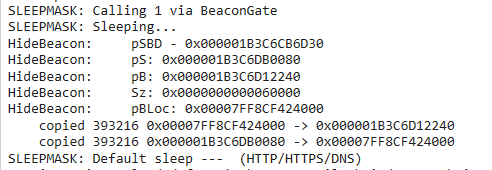

However, I find it more convenient to compile my BOF as an object-file in Release mode. Even if in Release mode, you can still access debug-style print statements by leveraging DLOGF to print anything you want at runtime. Define ENABLE_LOGGING in debug.h and put thos DLOGF statements everywhere to log what your BOF is doing once you run it within a debugger. Here is an example of my Sleepmask outputing some of those debug statements with values of various pointers I am using:

An important thing to be aware of is that this BOF is allocated separately from beacon. Within Cobalt Strike 4.10, following the examples given in the UDRL-VS (provided with the Community Kit), this memory is allocated via BudLoaderAllocateBuffer(), specifying a purpose being PURPOSE_SLEEP_MASK_MEMORY. You are free to allocate that memory the way you want, but bear in mind that if you keep the default, it will run from within a private RX memory ! BeaconGate is a double-edge sword. While it gives you the means to achieve better opsec, it can also backfire and achieve the opposite results by making your API calls to originate from a memory location which is more suspicious than the initial beacon memory space !

Note: Unlike the BOF examples above, this is part of Cobalt Strike so the code cannot be shared and the snippets will be minimalistic.

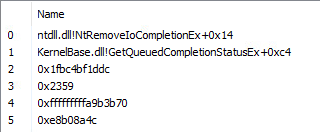

For instance, here is a beacon setup via Module Stomping. I am running ls and checking the callstack when the underlying Windows API is called:

![]()

Even if it ultimately leads back to unbacked memory (we’ll check this), the origin of the call is the stomped module winmsipc.

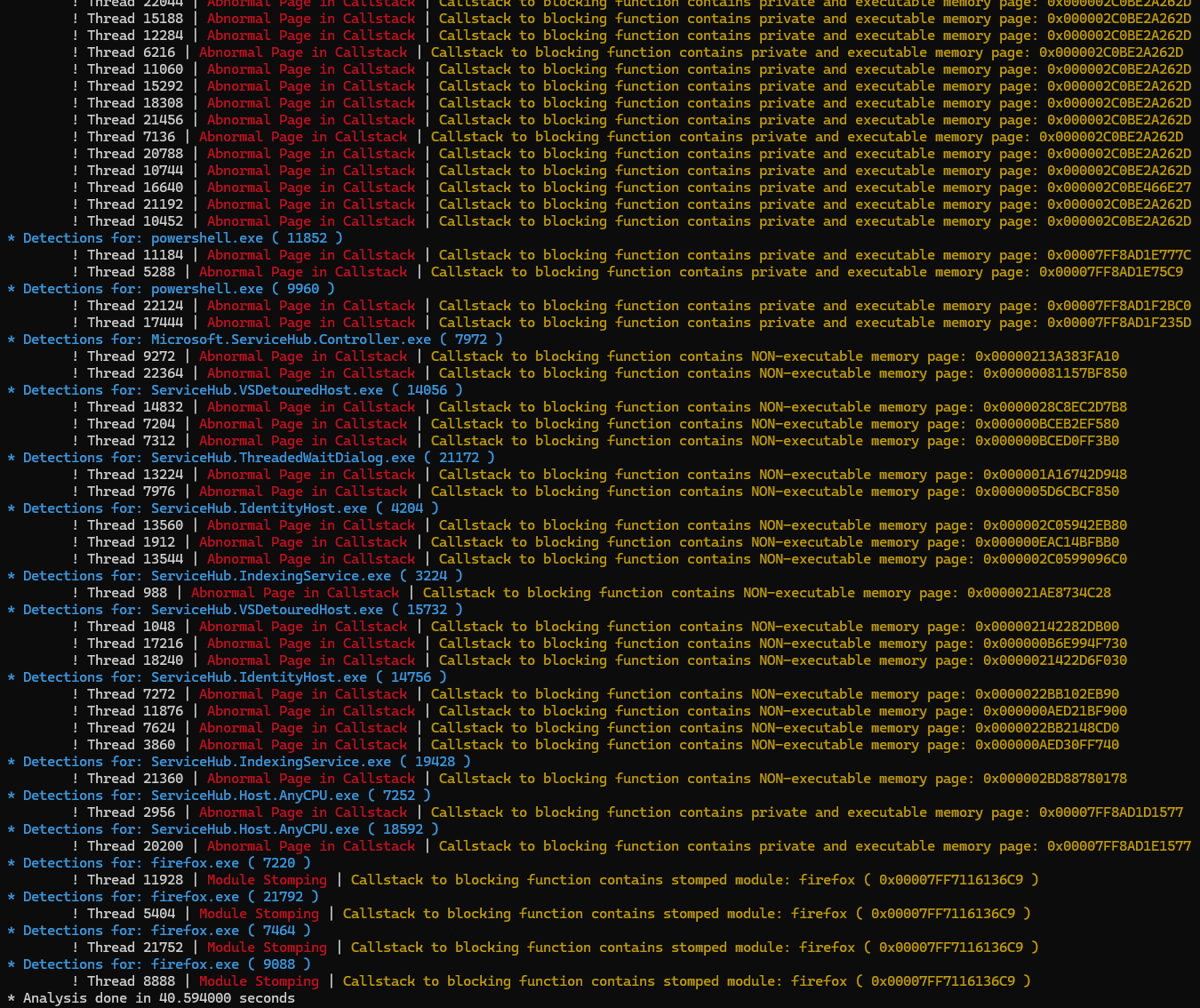

If I decide to use BeaconGate for InternetConnectA() (you define this in the Malleable profile via the beacon_gate{} directive, refer to the documentation), the call will directly originate from the BOF space, which, by default, is an unbacked RX memory page:

![]()

Implementing some custom Sleep

The two classic options for implementing the time delay in Sleepmasks are through Sleep() or WaitForSingleObject(). The latter has been known to be slightly stealthier (especially with Hunt-Sleeping-Beacon before it caught up with this, because of the different wait type (UserRequest) that would result from this call.

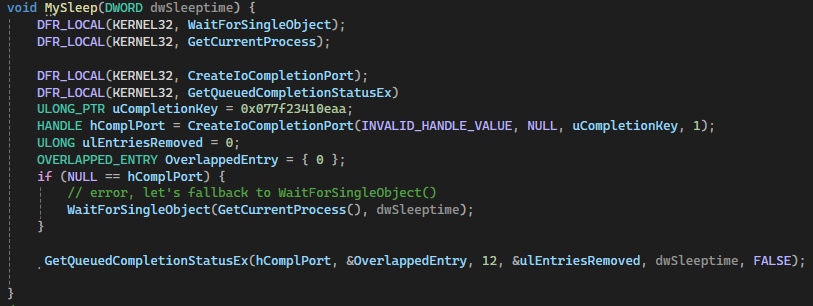

I propose an alternative which translates in a different wait type: WrQueue.

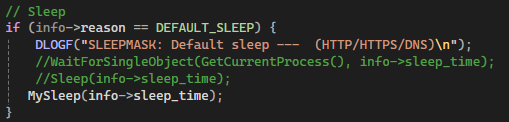

In the Sleepmask-VS template, you modify the sleeping function here:

MySleep() implementation relies on GetQueuedCompletionStatus() to implement a wait (which we know will timeout after a delay of our chosing) on an IO object. More details on this API here but what really matters is the fact that it can timeout, which is all that matters in that specific scenario:

As mentionned above, the blocking function is quite unusual and hopefully, less monitored:

It is still blocking, so Hunt-Sleeping-Beacon will catch it as it looks at anything blocking, but it will likely be less frowned upon by security products. Also, these types of IOCs are fairly common on a standard Windows environment:

Beacon User Data

Finally, I would like to quickly mention another useful feature that helped me implement a custom Sleepmask: the Beacon User Data “custom data”, which is a mechanism that allows you to share data between the various elements of your implant: your UDRL, beacon itself, and the Sleepmask.

The USER_DATA structure contains a custom field which you can use to store anything. As per the example “BUD Loader” provided in the Artifact kits, once defined, it is passed to beacon if you invoke it with DLL_BEACON_USER_DATA. In my case, it is storing an address on the Heap, created in the early steps by the UDRL, and the Sleepmask will use it to know where to look for certain things that are defined at runtime. You can see hints of this in the previous snapshots of the implant running with the debugger attached and logging various debug statements related to “hiding” or “unhiding” beacon. That particular implementation is not the point. The key feature here is the ability to share that type of information so that all the moving parts of the beacon can somehow communicate information to each other.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the intro, the 3-part series on the Cobaltstrike website contain all necessary information and is a must-read, although not straight-forward. The purpose of this article was to demonstrate actual examples of practical implementations using Cobalt Strike new features, and give pointers which will hopefully make it easier to look into the technical documentation.