EDIT January 10, 2025

[ Aaron Klotz (@dblohm7), an ex-Mozilla developer, reached out to me to explain that he worked on this in an effort to prevent third-party software from messing with Firefox (which was often the case, mostly via wild DLL injections or patching). His blog article at the time goes into more details. ]

While testing payloads, I stumbled across a security feature implemented within a popular browser, which acts like an EDR. By hooking a key Windows API, it checks thread creation at runtime and then decides whether this should run or not.

Failing to run RWX shellcode in a common browser

I have been testing a new type of process injection technique. It will probably be published on this blog in the near-future but the purpose here is not that injection technique in particular, but how I randomly came across a mechanism within a browser which acts like an EDR.

While injecting and executing successfully against something simple as notepad.exe is a nice start, the real test consists in confirming that this still works properly against more complex applications (.NET, large multi-threaded apps like browsers, etc…).

This is especially important for injection techniques since they will in some way interfere with the target process. Therefore, ensuring stability is key.

To that effect, I have been writing a simple shellcode in an RWX memory range, and then tried to get it to execute with a new technique against many common apps. It worked on all applications I tested except against one browser.

Note: this may be overzealous but to avoid legal issues I will not name that browser or the files/functions involved

It became evident that even when trying to execute the shellcode in a very trivial way (with CreateRemoteThread()), it still failed silently, with the thread being created but the shellcode never executed.

I initially thought this was caused by a technicality in the target process (browsers can implement funky things, modify native DLLs, etc…) but realized this actually looked like an intentional security feature, very much similar to what an EDR would do.

Hooking thread creation

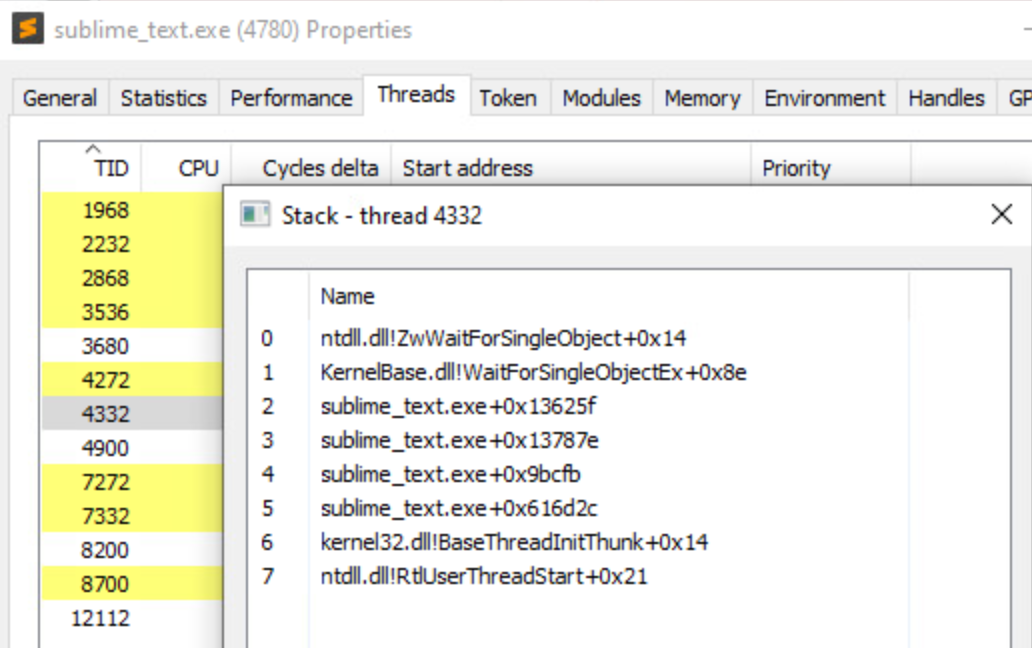

Similarly to what many security products have been doing in usermode through hooks, the browser is hooking BaseThreadInitThunk() to have visibility (and control) on what’s going on. This BaseThreadInitThunk call is one of the early steps involved in the creation of a thread, and you’ll find it in most callstacks in Process Hacker, for instance this is the one for my Sublime application right now:

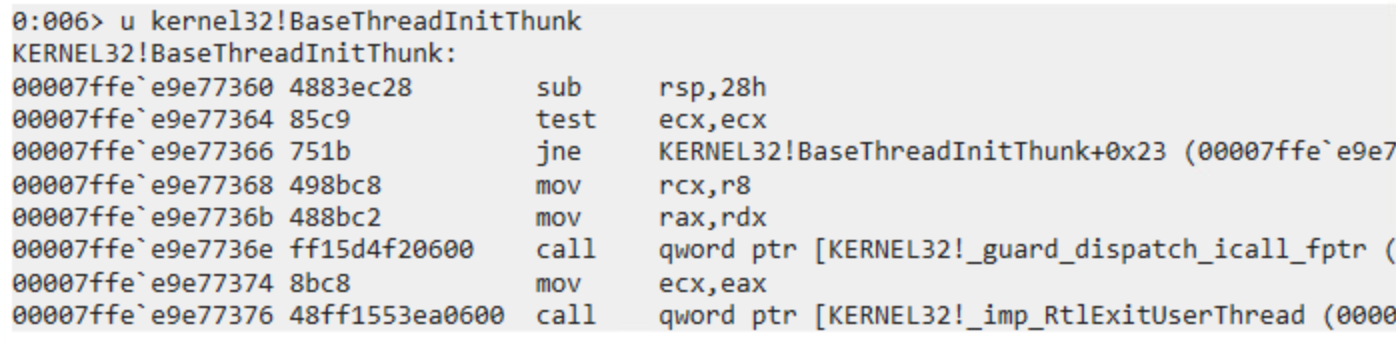

Here is the normal API in kernel32.dll:

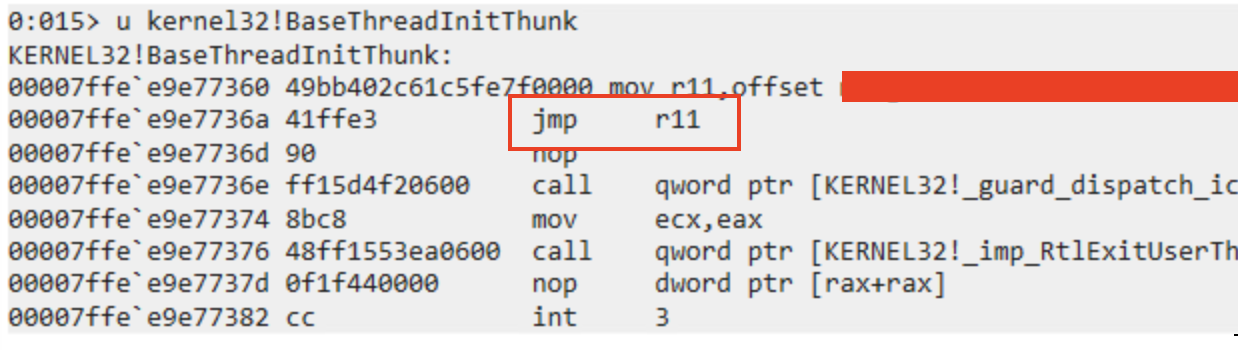

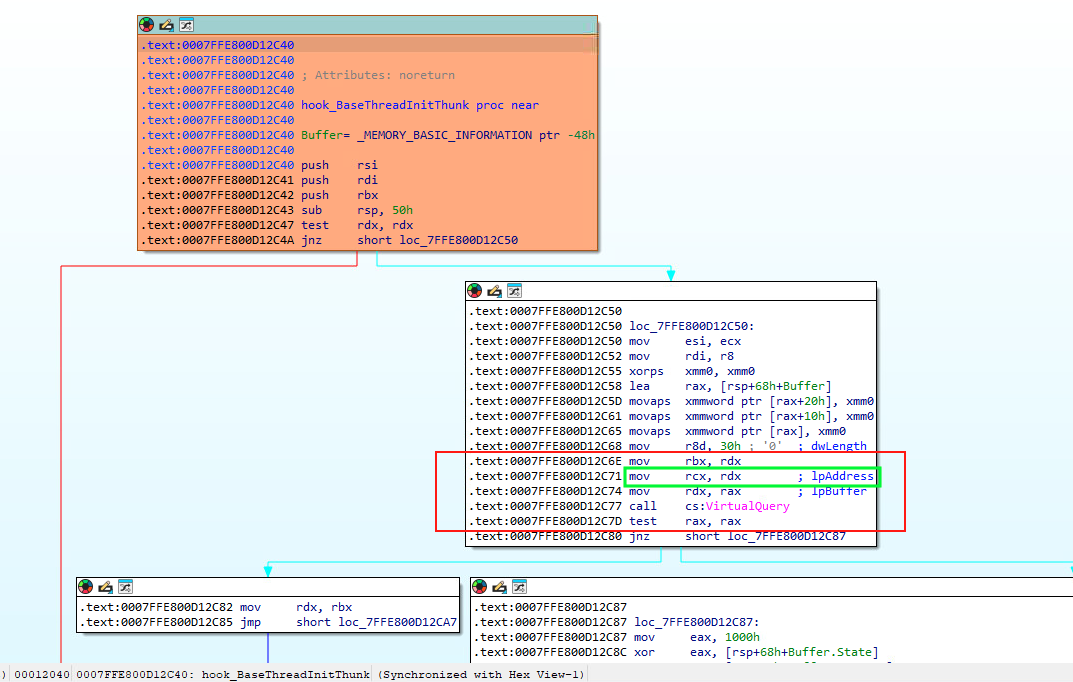

And here is the modified one used by our browser:

Any thread creation will be redirected through that jmp instruction, jumping somewhere into a custom third-party DLL that the browser loads, and for which I found very little information online (which prompted me to look deeper).

Do note that at this point, the intended thread creation address (where our shellcode is in memory), is stored in the rdx register.

Reverse-engineering the hook

As mentionned above, whatever thread creation takes place within the browser will first go through a custom check within one of its third-party DLL. That DLL is quite big and has a lot of exports. This makes me quite curious, but for what concerns us here, only one of those routines really matters. It is fairly simple and pretty much consists of a call to VirtualQuery() (in red), to retrieve the memory attributes for the address where our shellcode is:

Reminder on the arguments for this API call, it takes three arguments, moving the shellcode address into rcx (argument 1, in green).

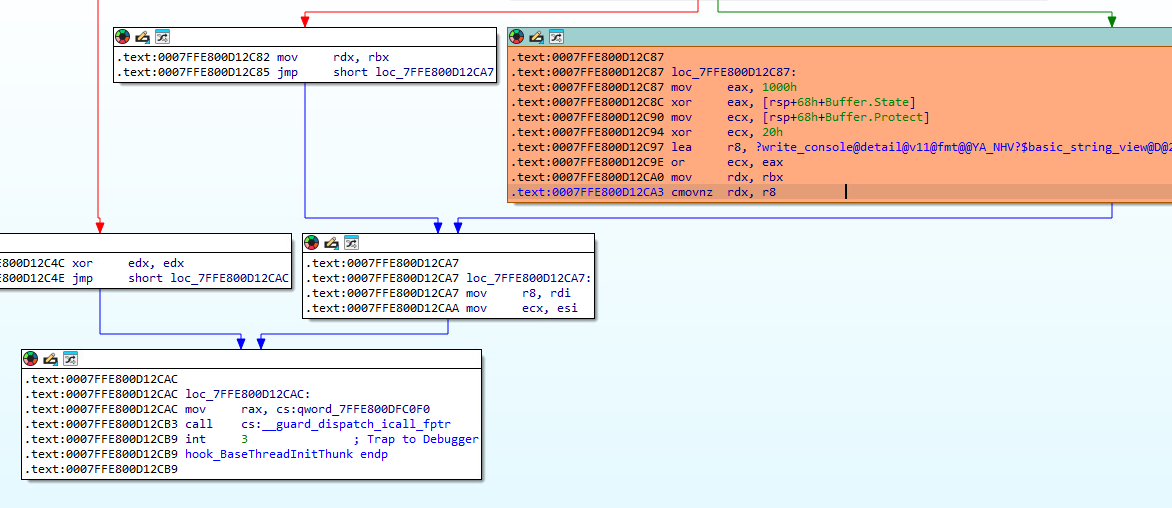

Further down the line, a few checks will verify if this memory address is a PAGE_EXECUTE_READ one (0x20 value as seen here).

Depending on the result (this is embedded in the cmovnz instruction), the following happens:

-

If yes, it does not interfere with the intended flow of execution and

rdx(which contains the shellcode to execute upon thread startup) is unchanged for the downstream code. -

If no, it then changes the thread start point and overwrites

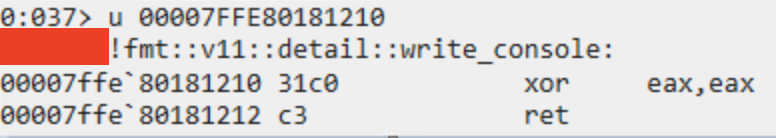

rdxit with whatever is inr8, which in this case is a kind of sinkhole which will just return immediately:

To summarize: if an RWX thread execution is attempted, it will be neutralized.

Conclusion

This check is fairly simple and basic to bypass (do not run in an RWX address), but I found this type of feature to be quite unexpected and worthy of a blogpost since I did not find any other reference to it online. I am not 100% sure it is purely a security control but this seems to be the only reasonable explanation. Browsers are one of these applications that have RWX sections in memory (do check this previous blogpost…), so this is probably a mitigating control which would make exploit development much harder in case an exploit chain attempted to leverage one of those RWX areas for execution. If you have any other theories or hypothesis… hit me up !